“I want knowledge. Not faith or conjecture, but knowledge. I want God to reach out his hand show His face, and speak to me.”

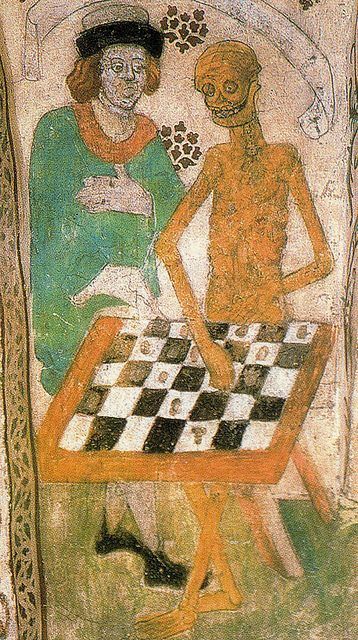

The images and feelings that would fill Bergman’s artistic career go back to his childhood when he would accompany his father as he preached in small churches around Stockholm. Here, he found himself distracted by his father’s austere sermons and would instead focus on the frescoes and paintings inside these old churches. Later in the early 1950’s, he would write a short, one-act play entitled Wood Painting, which used these images and characters, essentially writing the first draft of what many call Bergman’s masterpiece: The Seventh Seal (1957).

“In a wood sat Death, playing chess with the Crusader...But in the other arch the Holy Virgin was walking in a rose-garden, supporting the Child’s faltering steps, and her hands were those of a peasant woman.”

By the mid 1950’s Ingmar Bergman had become fairly well established and respected in the film world. The French Cahiers du Cinema critics were heavily influenced by Summer with Monika (1953) while his Shakespearean-like Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) was hailed at Cannes film festival winning the Jury Prize award. Interestingly, it was the success of the latter that convinced Bergman’s producer, Carl Anders Dymling, to approve the script for The Seventh Seal (1957). For years, he had rejected it as a result of its heavy and potentially alienating subject matter. This would prove to be quite a good business decision for the Svensk Filmindustri producer as the film would go on to receive extremely high praise internationally. French New Wave director and critic Eric Rohmer called it “one of the most beautiful films ever made” while American critic, Andrew Sarris, called it an “Existential masterpiece”.

For those unfamiliar with this 1957 film, a brief introduction might serve as helpful context for my musings. Bergman’s film follows the lives of a handful of Swedish women and men who are attempting to survive the Black Plague spreading throughout Europe. The main protagonist is Antonius Block, who is journeying back home with his squire, Jons, from the crusades in the Middle East. As the film begins, Block encounters Death and the two begin a chess game which will decide whether or not the knight will live or let Death take him as planned. Along the way, they meet young actors Mia and Jof, who along with their troupe leader Skat are touring the country side.

Considering the dual influence of the mediums of church painting and theatre, it is not surprising to hear Marc Gervais go so far as to say that the film is like “a medieval fresco worked out in time”, while additionally Birgitta Steene refers to it as “a cinematic tapestry”. As such, depending on one’s comfortability and experience with art house cinema, there are times where the script may feel a bit unnatural and scripted. But this is, of course, quite intentional: it is not necessarily trying to be a Realist film or represent reality as one experiences it. Instead, it is a film that plays equally with naturalism and formalism. Many have noted that each of the characters stand to represent an idea: Block the existentialist, Jons the atheist, Skat the hedonist, etc. Gervais expresses this idea in fuller detail:

“Just as the characters reflect each other, directly or obliquely, so the ideas that dominate the film arise from a tension of opposites: faith versus atheism, death versus life, innocence versus corruption, light versus darkness, comedy versus tragedy, hope versus despair, love versus infidelity, vengeance versus magnanimity, sadism versus suffering.”

Despite this however, one should not assume that this film stands as a polemic against any one worldview. At its core what this film seems to want to express is a call to life--whether that be the life of an atheist, a searcher, an artist. Life as enigma, in all of its obscurity and infinite complexity, is to be lived: with nature, with food, with family, with love.

Despite the Medieval setting in which this film takes place, this film holds a specific relevance to contemporary life: Bergman saw the world where the Black Plague stood as an apocalyptic sign as something particularly akin to the feeling of being alive in the Twentieth century. In the advent of the atom bomb, the world stood on the brink of extinction. While reflecting on the artistic perspective of the film, Bergman notes: “My intention has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter, with the same objective interest, with the same tenderness and joy. My beings laugh, weep, howl, fear, speak, answer, play, suffer, ask, ask. Their terror is the plague, Judgment Day, the star whose name is Wormwood. Our fear is of another kind but our words are the same. Our question remains.”

As I have mentioned in previous posts, a sequence which many have written about and should be taken notice of, is the strawberries and milk sequence. Here, in the midst of laments, fear of plague, flagellant spectacles, and death, stands a moment of brief, bright light. From the first sequence when Antonius Block steps from the sea, he is entranced with questioning, doubting, and his search for epistemic certainty--or at the very least comfort in what he can and cannot know. It is only when he meets Mia and Jof, and partakes in this small meal of wild strawberries and fresh milk that he begins to see life more simply. Life becomes, even if just for a moment, about living, it becomes about the creation of meaning, about personal responsibility in spite of, not because of, certainty.

Formally, the sequence itself is incredibly intricate. During a nearly exhaustive analysis of this sequence, Marc Gervais speaks of the rhythm and the editing as “confirm[ing] the feeling of spontaneity”--in other words the scene depicted, “all seems real, it has the feel of the rhythms of natural living”. This is essential for the later contrast with the thematic climax of the scene: “when the Knight, in a very close medium shot, raises the bowl of milk in a kind of offering, the effect is totally different. The moment flows with what one might term an iconic aura.” This formal change is felt viscerally, like a crescendo screaming of iconographic power.

This statement Bergman makes is not necessarily religious, but as it explicitly draws from religious symbols, it also cannot be separated from religion. Outside of the question of religion, it is an expression of life, of love, of family, not given meaning from external sources, but in the living itself. It is not the bread representing Christ’s body, it is a bowl of wild strawberries; and it is not the wine representing Christ’s blood, it is fresh milk--both these contrast in that they represent nothing other than what they are: sensory, natural, and of the earth. Birgitta Steene explains that “milk and wild strawberries are also private symbols in Bergman’s world, the Eucharist in a communion between human beings”. It is this key moment where Block puts words to this feeling:

I shall remember this moment. The silence, the twilight, the bowls of strawberries and milk, your faces in the evening light. Mikael sleeping, Jof with his lyre. I’ll try to remember what we have talked about. I’ll carry this memory between my hands as carefully as if it were a bowl filled to the brim with fresh milk. And it will be an adequate sign--it will be enough for me.

It is here that I wish to open up discussion on the topic of communication once again. This film then stands as the first point of entry for this series: man’s inability to communicate with the divine. Now, a small side note before I continue, regardless of one’s religious or non-religious beliefs, I do wish that the phrase “the divine” not dissuade interest. Instead, to see it as a symbol, a stand-in for objectivity or Truth. Antonius Block has lived his life in search of Truth—specifically referred to in this case as the Judeo-Christian “God“. However, on the other side of things, it is additionally important to note that the film makes no clear comment about the existence of God at all, only on the incommunicability and silence of the deity.

Here, the inability to communicate with Truth/God via language causes Block, and by extension Bergman, an incredible amount of sorrow. Existential misery directs the life which seeks this point of connection which may provide a bit of contentment. While I do not wish to belabor the point, what Block is in fact seeking is contact—specifically contact with certainty. Often, he talks of wanting God to touch him, speak to, and answer him while lamenting the being in the dark who seems to not hear or listen. It is thus not a coincidence that the strawberries and milk scene stands as the high point of Block’s contentment in the film: the physical, sensory, and tangible reality of being with Mia and Jof while eating and listening to calming music. It is here that we see the hope for hope in Bergman as opposed to the ostensible depression and cynicism many see. Gervais notes: “It is obvious, it seems to me that Bergman leans heavily on the side of a certain kind of affirmation of life, and perhaps, of meaningfulness.“ Thus we find his active brilliance, not just in the opening up of essential and existential questions, but in how he utilizes his own distrust of language to point to something deeper: the acceptance of nebulous contact with the physical.