“It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that cinema saved my life.”

Much like his cinematic compatriot Jean-Luc Godard, this quote from Francois Truffaut represents his deeply ingrained love and need for the cinema. Both were more than just film fans, their passion instead goes above and beyond into a lens with which to see and experience reality. This artistic medium becomes an all encompassing force that becomes the drive behind everything in life for these ‘young Turks’.

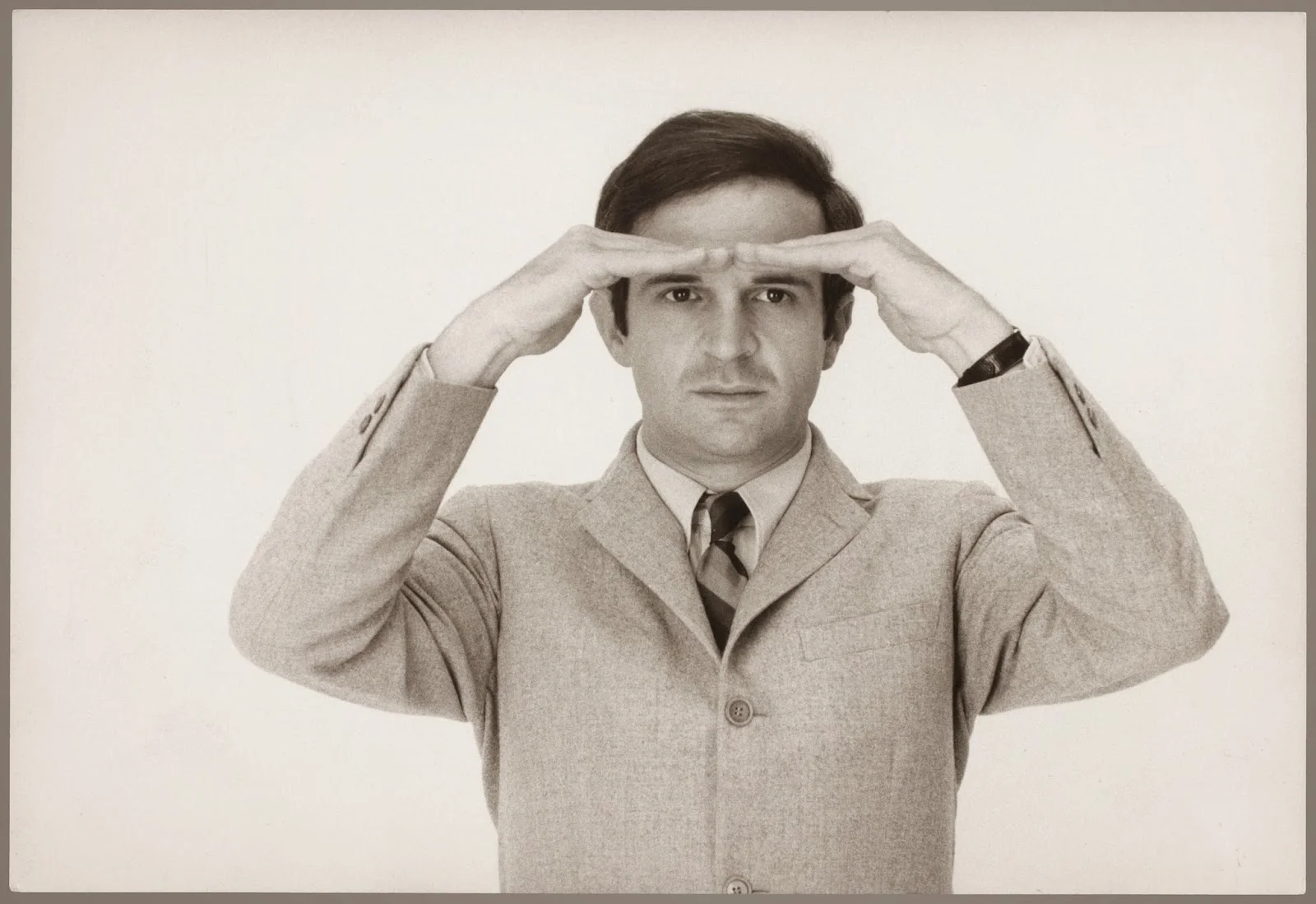

However, compared to Godard’s religio-philosophical turn towards cinema, Truffaut is a bit more psychological and self-focused: the necessity is in the act. Of course the themes and ideas contained within films and their forms were important, but at his core, his need to watch films was located in the act of experiencing them and his need to make films, in the act of making them. He thus represented a new type of person, as Sanche de Gramont noted: “Aside from being a much-admired film director, Truffaut is a charter member of a new species, the ‘homo cinematicus,’ who is concerned—to the exclusion of nearly all other pursuits—of life at 24 frames a second.”

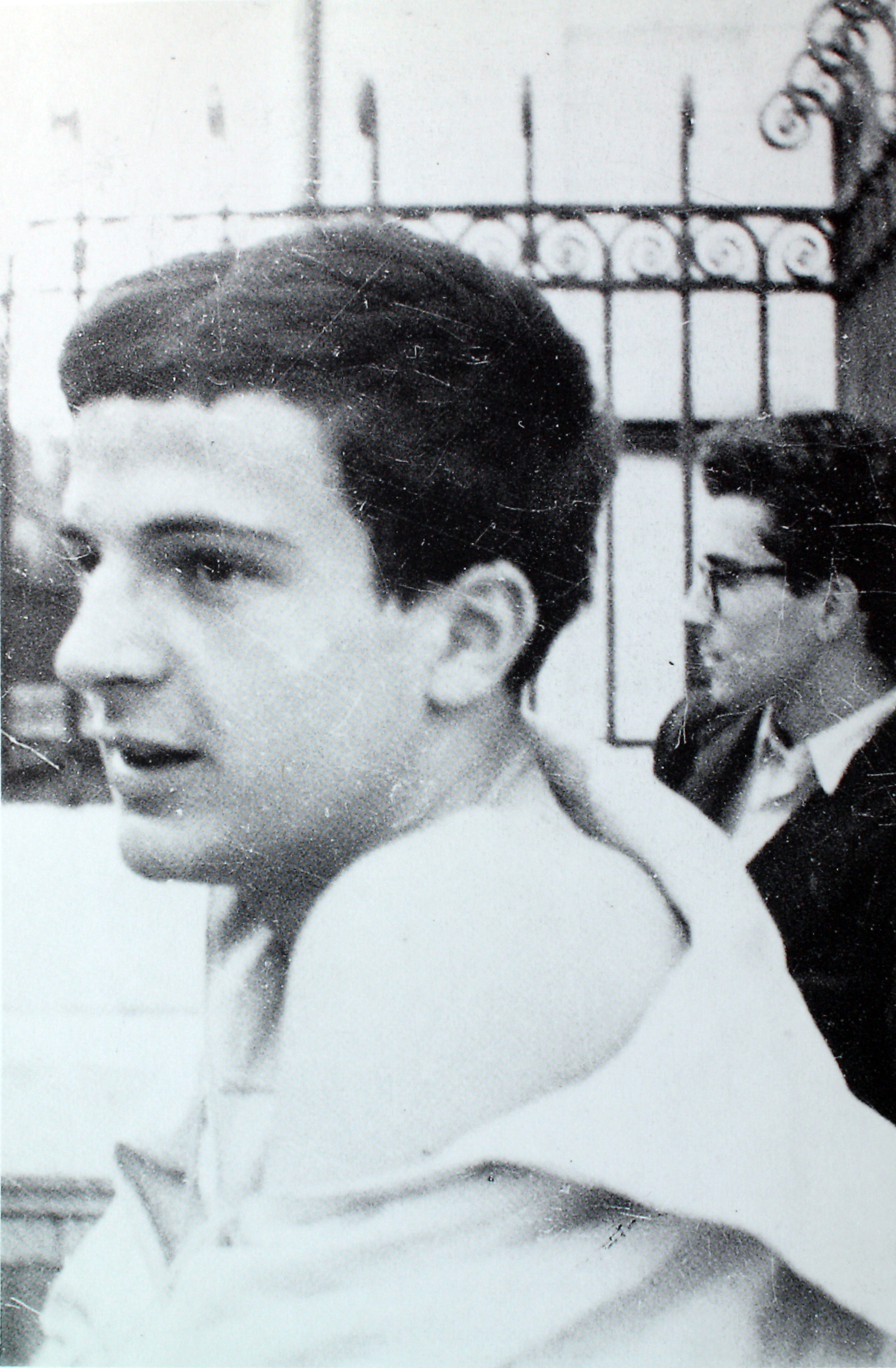

While much has been written about Truffaut’s biography--especially where cinematic exegesis is concerned--the essential details include being born in 1932, an illegitimate child to an unmarried 19 year old who was (apparently) rather uninterested in her son. Add to the list that he never knew his father, the mystery of Truffaut’s intense and personal need for cinema quickly unravels. Due to the instability of his early life, it is unsurprising to find the locus of his childhood within a rebellious sphere: playing hooky, sneaking out of the house, and misbehaving both at home and in school were commonplace for the young François. Consequently, he often found himself retreating from his ‘normal’ life into the cinema and it is here where he truly found not just a home, but a family.

When he was 14, the young film fanatic started his own cine-club—a very popular activity among Parisian intellectuals of the time. However, slated for his screenings were directly in competition with another cine-club that was led by none other than Andre Bazin. Known now as one of the fathers of the New Wave, Bazin was a film-critic who was known for his film theory of cinematic Realism (his major work being ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’). As fiery and passionate as he was about film, Truffaut had the gaul to go to Bazin and ask him to reschedule his screenings so there would not be overlap. Bazin declined, but admired the spirit of the young Truffaut and thus his path was set. Through Bazin, Truffaut was able to meet those who would eventually be his Cahiers cohort and cinematic family: Godard, Chabrol, Rivette, Rohmer, etc. French historian Jean-Michel Frodon summarizes this relationship quite well when he explains: “Truffaut found his true family in the cinema.”

In its direct and indirect associations then, family is a key to understanding Truffaut and his films. It has been argued that his relationship with his mother is a key factor to understanding him as artist, as well as his art. Anne Gillain explains her reading that,

Each of his films represents an unconscious questioning of a maternal figure who is distant, ambiguous, inaccessible...No matter how many films he makes, nor how many responses to the enigma she embodies, she always remains the source of Truffaut’s creative dynamic...A happy ending is unlikely, but emotion flows, and that is the essential thing.

As one could easily surmise, Truffaut’s films end up more narrative and person focused than Godard’s ideological and philosophical work. For an example one need only to look at his iconic debut, The 400 Blows (1959), to see his objective and documentarian-like approach to his protagonists. The film is heavily autobiographical focused on a young boy, Antoine Doinel, parsing through the difficulties of childhood related to his identity, family, friends, and society.

Truffaut himself admitted that he was perhaps the most conventionally psychological/narrative focused compared to the rest of his fellow New Wave directors—”More than the others, I am concerned with the characters.”. He was interested such narrative forms, particularly because he was interested in making people ‘feel’. To convey emotion was his goal and his drive for as long as he was making films. He confessed in 1976, “I’ve come to terms with the fact that the affective domain is the only thing I care about, and the only thing that interests me.” This specific type of human connection is also fairly unique within cinema (though the seed was certainly planted by the auteurs he admired) for he was interested in the whole person: the good, the bad, and the grey. His protagonists are hardly the Hollywood ‘hero’ of yesteryear, and even when they are ‘bad’ there is a distinctive lack of judgment placed upon them from the films and their maker—Truffaut explains: “I don’t assume any right to judge my characters: like Jean Renoir, I think that everyone has his reasons for behavior.”

“More than the others, I am concerned with the characters.”

- Francois Truffaut

Whether it be the cheating husband and father, Pierre Lachenay, the rebellious and typewriter stealing Antoine Doinel, or the elusive, demanding, and free-spirited Catherine, Truffaut fills the screen with genuine love and interest for his characters despite their varying degrees of despicability. Richard Neupert notes,

As Amis du film wrote in its review, the real novelty of The 400 Blows was that Antoine is not a tearful, fearful child but rather a real person and a survivor: “It takes enormous respect, love and intelligence for a director to create such a spontaneous and complex character…who is lost and abandoned but knows just how to take care of himself, naturally.”

The success of The 400 Blows stands as a kind of official starting point for the French New Wave. Along with Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour, both released in 1959, these two films opened the door for the success of the rest. At the Cannes film festival that year Truffaut won the best director prize, and made up over double the amount of the budget on international distributing rights alone. This is a testament to the film, partially due to the fact that the previous year Truffaut had been banned from Cannes as a result of what Michel Marie notes was a “vicious article attacking the French film industry.” The title of that article?

“The French Cinema is Crushed by False Legends.”

Another surprise of the success of the film is found in the already noted fact that Antoine is such a difficult character. Truffaut recalls some of the caution he received concerning the flawed boy: “The script-girl told me, ‘You know, the public will never accept this movie because you are showing a little loafer who steals money and hides it in a chimney.‘“ This then can perhaps stand as the staple of any Truffaut film: the good and the bad of everyone. Few people (if any) are truly ‘saints’ in Truffaut’s universe, instead most are wonderful ‘sinners‘. Extremely flawed men and women who make their way through the world, controlled and limited by whatever flaws, desires, or challenges they may be set up against. Paradoxically however, it is a testament to Truffaut that often when one thinks about his films, one does not think of the fairly dour endings. Instead, one thinks of the wonderful characters and the lasting love that one has fallen into by means of Truffaut’s cinema, compared to traditional narrative developments and conclusions.

In the end, as is fitting for the critic-turned-filmmaker, the work of an auteur is supposed to reflect the auteur himself/herself. Though there are of course many frameworks one can use to interpret his films (psychoanalytic, political, philosophical, etc.), what seems to be at the core of any interpretation is Truffaut himself. And here we find the fittingly poetic end:

The man who was saved by cinema did his part and returned the favor.